CTRL-F: Find the Facts, a contemporary verification skills program

At CIVIX, a civic education charity that creates experiential learning programs, we believe high-quality digital media literacy education should start from a young age in school.

It seems like every other headline these days is about false and misleading information online. From the Wild West of Elon Musk’s Twitter to advances in AI, to the ongoing climate crisis, every news event and issue is greeted by a cacophony of voices.

Perspectives based on facts and credible evidence are too often drowned out by hyperbole, spin, misunderstanding, and outright lies, in the case of disinformation, which is produced and distributed to cause intentional harm.

People are free to pick and choose which narratives to believe or to tune out all together.

The stakes are high and by now well-understood. False and misleading information can promote incorrect beliefs, obscure factual information, foster apathy, undermine faith in institutions, and threaten democratic systems.

These issues are large and structural, yet, as citizens, we require the tools, skills, and habits needed to navigate our increasingly complex and overwhelming information environment.

That’s why we built CTRL-F: Find the Facts, a contemporary verification skills program, created specifically to respond to the realities of the modern web.

While we may want to believe digital natives understand the information that comes through digital channels, there has been compelling research that shows this is not the case. A recent large-scale Canadian study by CIVIX shows middle- and high-school students are generally lost when it comes to evaluating the reliability of online sources and claims.

Students have been repeatedly shown to accept false and misleading content, while rejecting credible information, based on their own instincts or superficial analysis of the information itself.

When you stop and consider the failings of the most commonly taught information-evaluation techniques, these results become clearer.

The Checklist Problem

The most common approach to teaching source evaluation involves asking students to close-read information to look for clues about its reliability. This analytical approach is sometimes called ‘vertical reading,’ a term coined by the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG).

Vertical reading strategies most often take the form of a checklist of criteria for students to apply to information, ostensibly to discern its credibility. Tools including the popular CRAAP test ask students to identify superficial signals such as contact information, author names, advertisements, typos and to use these to make assessments about the quality of the information.

In practice, checklists can be time-consuming to apply, and yield conflicting results. It is also common for students to take a single metric and use it as a proxy for overall reliability. For instance, in our research we repeatedly saw a reliable news articles dismissed for having too many ads on the page, and a website for anti-LGBT lobby group accepted because the URL ended in .org.

Heuristics are appealing because they make things easy, but there is a cost for this.

Checklists are ubiquitous at every level of education, but they were not built for or suited to the modern web, and fail when applied there. Furthermore, this failure is not neutral. These techniques can cause harm, leading students to incorrect conclusions they feel confident in because they are using the strategies they’ve been taught.

This is particularly problematic given the context of online disinformation, as the checklist approach can unwittingly help those who intend to mislead. As Joel Breakstone et al of SHEG have observed:

“By focusing on features of websites that are easy to manipulate, checklists are not just ineffective but misleading. The internet teems with individuals and organizations cloaking their true intentions. At their worst, checklists provide cover to such sites.”

It’s common in education to learn that we can get to the bottom of a problem by thinking smartly, observing keenly, and applying critical thinking skills. When it comes to online information, however, the reality is that before we critically engage, we first need to contextualize.

The good news is that students can be taught simple skills to do this.

Lateral Reading with CTRL-F

CTRL-F: Find the Facts is a verification skills program that helps students in grades 7 to 12 learn how to read laterally, and build the habit of investigating information.

Lateral reading is simply the act of leaving a page where information is found to conduct simple research about it.

This is what professional fact-checkers have been found to do to quickly reach accurate conclusions about the reliability of online sources and claims. Any critical analysis takes place only after the key context is known.

Named for the keyboard shortcut for ‘find,’ CTRL-F is based on the idea that there are simple steps we can take to locate the information we need. The program was launched in 2020 and has since been used in thousands of classrooms across the country.

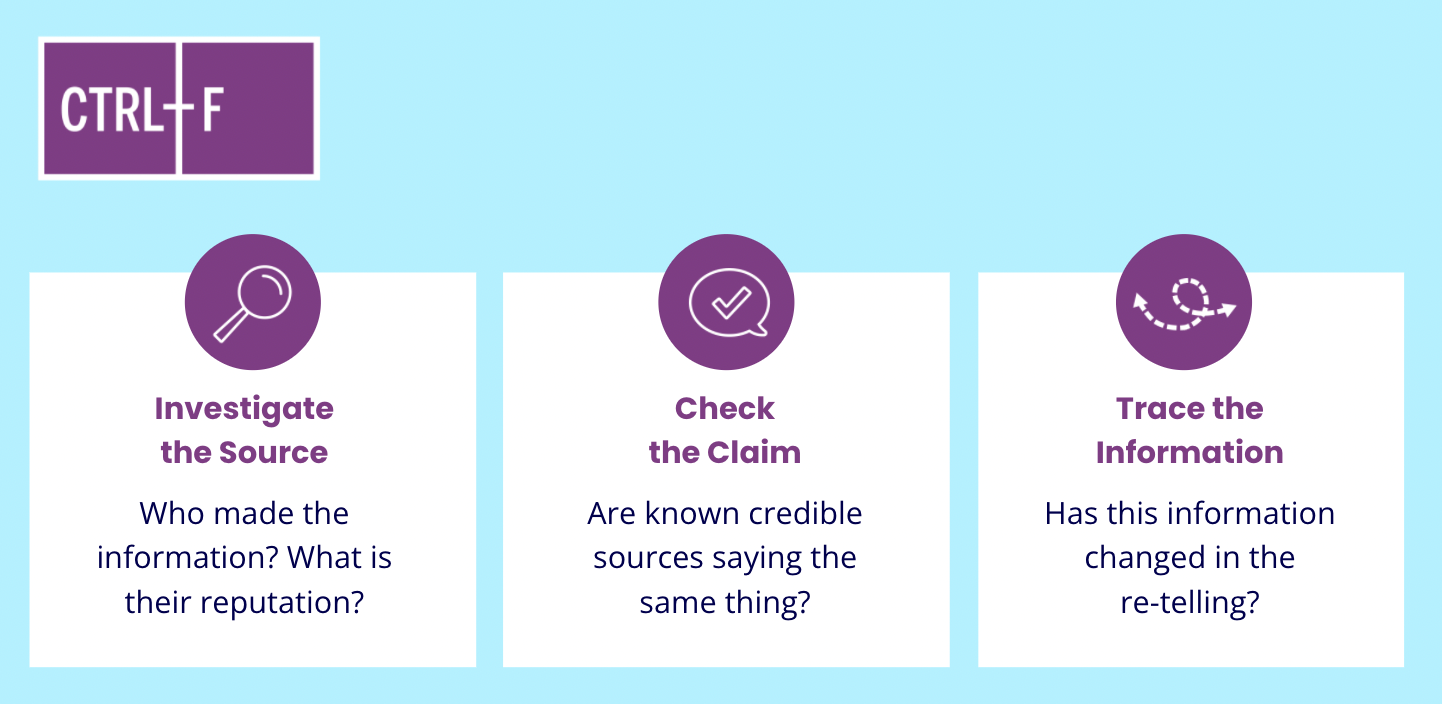

CTRL-F is centred around three key lateral reading skills:

Investigate the Source. Students learn to do quick checks of sources, primarily with the help of Wikipedia. We know Wikipedia is still controversial, but its reputation isn’t deserved. It’s an excellent starting point for checking the reputation of unfamiliar people and groups.

Check the Claim. Sometimes we just want to know if something we see or hear is true or not. In this case, we can use strategic keywords searches to see if a claim has been reported — or debunked — by a fact-checking site or professional news organization.

Trace the Information. False and misleading information is often content that’s been altered, misrepresented, or taken out of context. Trace the Information is the ‘broken telephone’ skill. Here students learn to trace claims, quotes, and images back to the original source to see how or if they’ve been changed.

In practice, these skills are packaged for classroom use by teachers, with expert videos and interactive real-world example activities. The program is available in English and French, designed for students in grades 7 to 12, and takes approximately seven hours to complete.

All of the materials are available free (with registration) at ctrl-f.ca. For a sample of what the programming looks like, this practice site lays out each part of the learning and allows visitors to try their hand at the checks.

The CTRL-F skills are simple, but powerful when applied. And while we know we can’t look up every piece of information we see online, getting in the habit of doing quick checks before we believe or share something reduces information pollution and fosters informed citizenship.

Measuring the CTRL-F Impact

Over the 2020/21 school year CIVIX partnered with expert researchers to study 2,324 Canadian students’ information-evaluation skills, before and after completing the CTRL-F program.

Among the key findings from the “Digital Media Literacy Gap” report:

- CTRL-F dramatically improves students’ ability to read laterally. Students read laterally 11% of the time at pretest versus 59% at posttest.

- CTRL-F helps students locate key context. Students were able to identify the agenda of an advocacy group just 6% of the time at pretest. This number rose sixfold to 31% at posttest. On delayed posttest, it increased again to 49%.

- Lateral reading helps students get the right answer for the right reasons. Before CTRL-F, students referenced meaningful contextual information just 9% of the time to support a correct answer. On post-test, this number jumped to 50%.

- The CTRL-F skills stick. A delayed posttest delivered six weeks following the end of the CTRL-F curriculum showed no erosion in the use of lateral reading strategies.

There is still work to be done, but these results demonstrate the promise and potential of the skills at the heart of CTRL-F.

Democracy needs a new generation of informed citizens with the capacity to evaluate the political and social information that reaches them through digital channels. And for this, we need to transform the way digital media literacy is taught by adopting evidence-based approaches.

For more information, visit civix.ca and ctrl-f.ca.